ISP 1510: INTERMEDIATE READING AND

WRITING

Interdisciplinary Studies Program,

Wayne

State University

Detroit, Michigan, USA

|

If

you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the

tools) to write. Simple

as that.—Stephen

King |

Term: Fall 2003 (Sept 2-Dec. 18, 2003)

Section: 001

Credits: 4

Location: 222 Cohn

Time: Monday, 9:35-1:15 a.m.

Contact Information for Moti Nissani (class instructor):

|

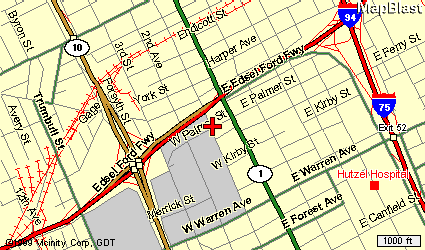

Work Address (but please use e-mail or my home address below—I’ll get it faster this way): Interdisciplinary Studies Program, Rm. 2134, 2nd floor, 5700 Cass, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202 |

Home Address: 28645 Briar Hill, Farmington Hills, MI 48336 E-Mail: aa1674@wayne.edu Tel.: 248-427-1957 (home; OK to call any day, 12:00 noon-9:00 p.m.) Homepage: www.is.wayne.edu/mnissani/ |

General Education Requirements: Wayne State is committed to imparting quality well-rounded education to all its undergraduates. As part of this goal, the university created a set of requirements (e.g. a minimum of one course each in foreign culture and the life sciences), that each undergraduate must meet. This course (ISP 3510) satisfies general education requirements in intermediate composition (IC)..

Text: Coursepack (to be sold in class—$10—please make check payable to Moti Nissani, not WSU!)

Grading.

This

will be based on written assignments (50% ), tests (20%), attendance

(20%), and

contributions to class. There

are

basically four grading categories:

1. An

A (or A-) can only be earned by excellent readers and writers (these

skills

cannot be acquired in one semester!) who submit all their assignments on

time,

make significant contributions to class, and attend all required

sessions and

appointments. 2. Anyone

with excellent

attendance

Grading.

This

will be based on written assignments (50% ), tests (20%), attendance

(20%), and

contributions to class. There

are

basically four grading categories:

1. An

A (or A-) can only be earned by excellent readers and writers (these

skills

cannot be acquired in one semester!) who submit all their assignments on

time,

make significant contributions to class, and attend all required

sessions and

appointments. 2. Anyone

with excellent

attendance

TITLES

One more reminder before you start writing: Every assignment in this class—and eventually, your senior essay—must be preceded by a title. Have you ever read a book that has no name? Seen a title-less film? Met a nameless person?

A title-less assignment falls, more or less, into one of these very sorry categories. Why? Well, first, a good title tells the reader what to expect. Second, a good title is an invitation to the reader to go on reading. It is perhaps one of the most important parts of a piece of writing.

For an instructor, especially, a title is a treasure trove. I once graded titles only, then graded the paper itself. In almost all cases the two grades were uncannily close. Why? Because a good title shows that the student understood what the assignment was. And usually this is the biggest problem—most people write about what they imagine the assignment to be, instead of finding out what it really is.

Now, what is a title? If you are working on Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls’could that be the title of YOUR essay? Absolutely not!!! Why, because that's the name of Hemingway’s book, not of your essay. Also, how does your reader know what it is that you're trying to do with this book? Are you going to review it? Use it as a source of information about the Spanish Civil War? Explore the impact of that war on novelists? Explain the UK’s and USA’s pro-fascist policies? So this is better:

A Review of Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls.

by

[Give your name here]

A title, especially if it involves creative writing, can be more imaginative and inviting, relying often on subtitles. For instance, Silent Bells: A Review of Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls. But for the moment, for the kinds of assignments we are doing in the first few weeks of this class, a merely informative title will do.

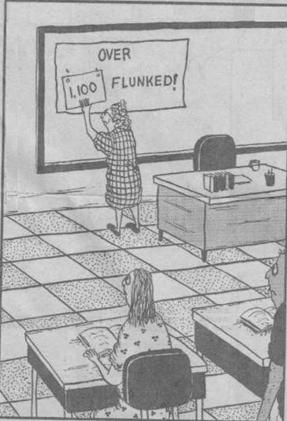

record, who shows improvement throughout the course, submits all assignments on time, contributes to class activities, and is willing to undertake some extra reading and writing assignments, can earn a B (contact me for details). 3. With no extra work and effort, your performance alone will determine your grade. 4. Students who fail to submit and re-submit all assignments or who miss more than two scheduled classes will fail the class.

Teaching

Philosophy.

1 I happen to believe that we only learn what we want to learn. You can lead a student to the library, but you can’t make her read! Learning is an internal process that depends, above all, on motivation. That is one reason this class will appear to you odd at times—I go out of my way to make the material interesting and relevant.

2 To learn anything you must work hard. After a hard day’s work, it’s easier to vegetate in front of your TV than read and write. I use grades to help you give your TV the slip.

3 I strongly believe that the main value of education is intellectual freedom. The more you learn, the better you understand the world around you and yourself. You soon come to realize that you often have many more choices than you have ever imagined. Reading—not writing, watching animal shows on TV, or taking university classes—is the best, perhaps the only, road to freedom. So, throughout the term I shall try to arouse your interest in good literature (the best kind of reading there is).

4 4. Moreover, in addition to being a reading class, this class, as its name suggests, is a writing class. Now, how do you become a good writer? By consulting dictionaries? NO. By studying grammar? NO! By diagramming sentences? NO and NO and NO again. By taking writing classes? Well, that will help to improve your writings, but that by itself is not going to do the trick. To write well, you must read, and read, and read some more. I’ve actually written a very long paper just to vent some of my frustrations on the subject, and you can read that paper in your local library (DPL and Purdy subscribe to that journal), or on the internet (https://www.drnissani.net/mnissani/pagepub/LANGUAGE.HTM). Instead of citing myself though, I’ll merely cite the opinion of 2 recognized experts:

It

is only through reading that anyone can learn to

write. The only possible

way to learn

all the conventions of spelling, punctuation, capitalization,

paragraphing,

even grammar, and style, is through reading.

Authors teach readers about writing (Smith, 1988, p.

177). Reading

is the only way . . .

we

become good readers, develop a good writing style, an adequate

vocabulary,

advanced grammar, and the only way we become good spellers (Krashen,

1993, p. 23).

Ideally, you would have started to read by age 5 (Oprah Winfrey, as you will soon hear, started at age 3!), and never let it go. But most people aren’t that lucky. So, if you are a reader already, this class will further enhance your love of reading and ability to better understand what you read. If you are not a reader, and if you give yourself a chance, this class will help turn you into one.

How to Submit Assignments? Either through e-mail (aa1674@wayne.edu) anytime before the assignment is due or double-spaced, typed paper submissions on the due date.

Individual Consultations with Class Instructor: Some instructional goals can only be met in face to face meetings, which will be scheduled at least once throughout the term. Make sure to bring all your work with you and to not skip appointments! Showing up on time is a formal class requirements, and failure to do so will strongly and adversely affect your final grade!

A Note to Advanced Writers: This class fosters basic reading and writing skills, which you may already have. In such cases, you and I will sit together and create an individualized program of instruction (e.g., emphasis on creative writing, or science writing, or newspaper writing, or . . .).

Rewrites and Make-ups: One important aspect of becoming a better reader and writer is re-writing. The process begins prior to submission—after you finish the first draft of your paper, you carefully edit it. You then give a friend or a fellow student the revised draft, get their comments, and edit again. Then it’s my turn. After receiving my comments, you submit the final version of your paper.

Log of Lapses. Every time you get your paper back from me, you’ll notice some errors that have been made by you and corrected. When you agree with any comment, you’ll change the second draft of your paper accordingly, of course. But you’ll also create a record of such blunders in your own, personalized, Log of Lapses. That log will look something like this:

Log of Lapses

Kathleen Asselin

|

Assignment |

I wrote |

I should have written |

|

Mr. Ryan |

|

Their way |

|

Mr. Ryan |

Five |

Five guitars |

|

Mr. Ryan |

I like ice cream to |

I like ice cream too |

|

Ballad |

These steps |

These steps are broken |

|

Shep |

In my summary of the story I overlooked

Shep’s Hobby—the main point of the story |

I should have explained what Shep’s hobby was and how it survived the narrator’s outburst. |

You’ll always have this log by your side when you do work for this class (and under your pillow when you go to bed—this goes without saying). Bring this log to every session, and update it during class too.

This comedy of errors may sound like busywork. In class I’ll try to convince you that it isn’t by telling you the story of Demosthenes, a stutterer who became one of the world’s greatest orators—some of his speeches are still preserved in the library, more than 23 centuries after they had been delivered! To get there, believe me, he had to pay a much higher price than living with a “Log of Lapses” for one semester.