Flax-Golden Tales

unit eleven: Critical and

Creative Thinking

The Stub-Book

Pedro Antonio de Alarcón

(Spain, 1833-1891)

he action

begins in Rota. Rota is the

smallest of those pretty towns that form the great semicircle of the bay of Cádiz. But

despite its being the smallest, the grand duke of Osuna

preferred it, building there his famous castle, which I could describe stone by stone. But now we are dealing with neither castles nor dukes, but with the fields

surrounding Rota, and with a most humble gardener,

whom we shall call Uncle Buscabeatas

though this was not his true name.

From the fertile fields of Rota, particularly its gardens, come the fruits and vegetables that fill the markets of Huelva and Seville.

The quality of its tomatoes and pumpkins

is such that in Andalusia the people of Rota are always referred to as

pumpkin-

and tomato-growers, titles which they accept with pride.

And, indeed, they have reason to be proud; for the fact is that the soil of Rota, which produces so much, that is

to say, the soil of the gardens, that soil which yields three or four crops a

year, is not soil, but sand, pure and clean, cast up by the ocean, blown by the furious west winds and thus scattered over the entire region of Rota.

But the ingratitude of nature is here more than compensated for by the constant diligence of man. I have

never seen, nor do I believe there is in all the

world, any farmer who works as

hard as the farmer of Rota. Not

even a tiny stream runs

through those melancholy fields. No

matter! The

pumpkin-grower has made

many wells from which he draws the precious liquid that is the lifeblood of his vegetables. The tomato-grower spends half his life seeking substances which may be used as fertilizer. And when he has both elements, water and

fertilizer, the gardener of Rota begins to fertilize his tiny plots of ground, and in each of them

sows a tomato-seed, or a

pumpkin pip which he then waters by hand, like a person who gives a child a drink.

From then until harvest time, he attends daily, one by one, to the plants which grow there, treating them with a love only comparable to that of parents for children.

One day he applies to such a plant a bit of fertilizer; on

another he pours a pitcherful of water; today he kills

the insects which are eating up the leaves; tomorrow he

covers with reeds and dry leaves those plants which cannot

bear the rays of the sun, or those which are

too exposed to the sea winds. One day, he counts the stalks, the flowers, and even the fruits of the earliest ripeners; another day, he talks to

them, pets them, kisses them, blesses them, and even

gives them expressive names in order to

tell them apart and individualize

them in his imagination.

Without exaggerating, it is now a proverb (and I have often heard it repeated in

Rota) that the gardener of that region touches with his own hands at least forty times a day every tomato plant

growing in his garden. And this explains why the gardeners of that locality get to be so bent over

that their knees almost touch their chins.

Well, now, Uncle Buscabeatas was one

of those gardeners. He had begun to stoop at the time of the

event which I am about to

relate. He was already sixty years

old . . . and had spent

forty of them tilling a garden near the shore.

That year he had grown some enormous pumpkins that were already beginning to turn yellow, which meant it was

the month of June.

Uncle Buscabeatas knew them perfectly by

color, shape, and even by name, especially the forty fattest and yellowest, which were already saying cook me.

“Soon we shall have to part,” he said tenderly, with a melancholy look.

Finally, one afternoon he made up his mind to the

sacrifice and pronounced the dreadful sentence.

“Tomorrow,” he said, “I shall cut these forty and take

them to the market at Cádiz. Happy is

the man who eats them!” Then he returned home at a leisurely

pace, and spent the night as anxiously as a father whose

daughter is to be married the following

day.

“My poor pumpkins!” he would occasionally sigh, unable to sleep. But

then he reflected and concluded by saying, “What

can I do but sell them? For that I raised them!

They will be worth at least fifteen duros!”

Imagine, then, how great was his astonishment, his fury

and despair, when, as he went to the garden the next

morning, he found that, during the night, he had been robbed of his forty

pumpkins. He began calculating

coldly, and knew that his pumpkins could not be in Rota,

where it would be impossible to sell

them without the risk of his

recognizing them.

“They must be in Cádiz, I can almost see them!” he

suddenly said to himself. “The

thief who stole them from me last night at nine or ten o’clock, escaped

on the freight boat .... I’ll leave for Cádiz this morning on the hour boat, and

there I’ll catch the thief and recover the daughters of my toil!”

So

saying, he lingered for some twenty minutes more at

the scene of the catastrophe, counting the pumpkins that were missing,

until, at about eight o’clock, he left for the

wharf.

Now the hour boat was ready to leave.

It was a small craft which carries passengers to Cádiz every morning at

nine o’clock, just as the freight boat

leaves every night at twelve, laden with fruit

and vegetables.

The former is called the hour boat

because in an hour,

and occasionally in less time, it

cruises the thirty-eight kilometers separating Rota from Cádiz.

It was, then, ten-thirty in the morning when

Uncle Buscabeatas

stopped before a vegetable stand in the Cádiz market, and said to a policeman who accompanied him:

“These are my pumpkins! Arrest that man!” and pointed

to the vendor,

“Arrest

me?” cried, the latter, astonished and

enraged. “These pumpkins are mine; I bought them.”

“You can tell that to the judge,” answered

Uncle Buscabeatas.

“No, I won’t!”

“Yes, you will!”

“You old thief!”

“You old scoundrel!”

“Keep a civil tongue. Men shouldn’t

insult each other like that,” said the policeman very calmly, giving them each a punch in the chest.

By this time several people had gathered, among them the

inspector of public markets. When

the policeman had informed the inspector of

all that was going on, the latter

asked the vendor in accents majestic:

“From whom did you buy these pumpkins?”

“From

Uncle Fulano, near Rota,” answered the

vendor.

“He

would be the one,” cried Uncle Buscabeatas. “When his own garden, which is very

poor, yields next to nothing, he robs

from his neighbors’.”

“But, supposing your forty pumpkins were stolen last

night,” said the inspector, addressing the gardener, “how do you know that

these, and not some others, are yours?”

Well,” replied Uncle Buscabeatas, “because I know them as well as you know your daughters, if you have any. Don’t you see

that I raised them? Look here, this one’s name is Fatty; this one, Plumpy Cheeks; this one, Pot Belly; this

one, Little Blush Bottom; and this one, Manuela,

because it reminds me so much of my youngest daughter.”

And the poor old man started weeping like a child.

“That is all very well,” said the inspector, “but it is not enough for the law that you recognize your pumpkins. You must identify them with

incontrovertible proof. Gentlemen, this is no laughing matter. I am a lawyer!”

“Then you’ll soon see me prove to everyone’s satisfaction,

without stirring from this spot, that these pumpkins were raised in my garden,” said Uncle Buscabeatas.

And throwing on the ground a sack he was holding in

his hand, he kneeled, and quietly began to untie it. The curiosity of those around

him was overwhelming.

“What’s he going to pull out of there?” they all wondered.

At the same time another person came to see what was going on in that group and when the vendor saw him, he

exclaimed:

“I’m glad you have come, Uncle Fulano. This man says that the pumpkins you sold me last night were stolen. Answer ...”

The newcomer turned yellower than wax, and tried to

escape, but the others prevented him, and the inspector himself ordered him to

stay.

As for Uncle Buscabeatas, he had

already faced the supposed thief, saying:

“Now you will see something good!”

Uncle Fulano, recovering his presence of mind, replied:

“You are the one who should be careful about what you

say, because if you don’t prove your accusation, and I know you can’t, you will go to jail. Those pumpkins were mine; I raised them in my garden, like all the others I brought to Cádiz this year, and no one could prove I didn’t.”

“Now you shall see!” repeated Uncle

Buscabeatas, as he finished untying the sack.

A multitude of green stems rolled on the ground, while the old gardener, seated on his heels, addressed the

gathering as follows:

“Gentlemen, have you never paid taxes? And haven’t you seen that green book the tax-collector has, from which he cuts receipts, always leaving a stub

in the book so he can

prove afterwards whether the receipt is counterfeit or not?”

“What you are talking about is called the stub-book,”

said the inspector gravely.

“Well, that’s what I have here: the stub-book of my

garden; that is, the stems to which these pumpkins were

attached before this thief stole them from me.

Look here: this stem belongs to this pumpkin. No one can deny it . . . this

other one . . . now you’re getting the idea . . . belongs to this one . . . this thicker one . . . belongs to

that one . . . exactly! And this one to that one .

. . that one, to that one over there . . .”

And as he spoke, he fitted the stem to the pumpkins, one by one. The spectators were amazed to see that

the stems really fitted the pumpkins exactly, and

delighted by such strange proof, they all began to help Uncle Buscabeatas, exclaiming:

“He’s right! He’s right! No doubt

about it. Look: this one belongs here . . .

That one goes there . . .

That one there belongs to this one . . . This one goes there . . .”

The laughter of the men mingled with the catcalls of

the boys, the insults of the women, the joyous and triumphant tears of the old gardener, and the shoves the

policemen were giving the convicted thief.

Needless to say, besides going to jail, the thief was compelled

to return to the vendor the fifteen duros

he had received, and the latter handed the money to Uncle Buscabeatas, who left for Rota very pleased with himself,

saying, on his way home:

“How beautiful they looked in the market! I should have brought back Manuela to eat tonight and kept the seeds.”

9

Mr. Know-All

W. Somerset Maugham (England,

1874-1965)

was prepared to dislike Max Kelada even before I knew him.

The war had just

finished and the passenger traffic in the ocean going liners was heavy. Accommodation was very hard to get and

you had to put up with whatever the agents chose to offer you. You could not hope for a cabin to

yourself and I was thankful to be given one in which there were only two berths. But when I was told the name of my

companion my heart sank. It

suggested closed portholes and the night air rigidly excluded.

It was bad enough to share a cabin for fourteen days with anyone (I was going

from San Francisco to Yokohama), but I should have looked upon it with less

dismay if my fellow passenger’s name had been Smith or Brown.

was prepared to dislike Max Kelada even before I knew him.

The war had just

finished and the passenger traffic in the ocean going liners was heavy. Accommodation was very hard to get and

you had to put up with whatever the agents chose to offer you. You could not hope for a cabin to

yourself and I was thankful to be given one in which there were only two berths. But when I was told the name of my

companion my heart sank. It

suggested closed portholes and the night air rigidly excluded.

It was bad enough to share a cabin for fourteen days with anyone (I was going

from San Francisco to Yokohama), but I should have looked upon it with less

dismay if my fellow passenger’s name had been Smith or Brown.

When I went on board I

found Mr. Kelada’s luggage already below. I did not like the look of it; there

were too many labels on the suitcases, and the wardrobe trunk was too big. He had unpacked his toilet things, and I

observed that he was a patron of the excellent

Monsieur Coty;

for I saw on the

washing-stand his scent, his hairwash and his brilliantine. Mr.

Kelada’s brushes, ebony with his monogram in gold, would have been all

the better for a scrub. I did not

at all like Mr. Kelada. I made my way into the smoking-room. I called for a pack of cards and began

to play patience. I had scarcely started before a man came

up to me and asked me if he was right in thinking my name was so and so.

“I am Mr.

Kelada,” he added, with a smile that showed a row of flashing teeth, and

sat down.

“Oh, yes, we’re sharing

a cabin, I think.”

“Bit of luck, I call it. You never know who you’re going to be

put in with. I was jolly glad when

I heard you were English. I’m all

for us English sticking together when we’re abroad, if you understand what I

mean.”

I blinked.

“Are you English?” I

asked, perhaps tactlessly.

“Rather.

You don’t think I look like an American, do you? British to the backbone,

that’s what I am.”

To prove it, Mr. Kelada took out of his pocket a passport and airily waved it

under my nose.

King George has many

strange subjects. Mr. Kelada was short and of a sturdy build,

clean-shaven and dark skinned, with a fleshy, hooked nose and very large

lustrous and liquid eyes. His long

black hair was sleek and curly. He

spoke with a fluency in which there was nothing English and his gestures were

exuberant. I felt pretty sure that

a closer inspection of that British passport would have betrayed the fact that

Mr. Kelada was born under a bluer

sky than is generally seen in England.

“What will you have?” he

asked me.

I looked at him

doubtfully. Prohibition was in force and to all

appearances the ship was bone dry.

When I am not thirsty I do not know which I dislike more, ginger ale or lemon

squash. But Mr. Kelada flashed an oriental smile at me.

“Whisky and soda or a

dry martini, you have only to say the word.”

From each of his hip

pockets he furnished a flask and laid it on the table before me.

I chose the martini, and calling the steward he ordered a tumbler of ice

and a couple of glasses.

“A very good cocktail,”

I said.

“Well, there are plenty

more where that came from, and if you’ve got any friends on board, you tell them

you’ve got a pal who’s got all the liquor in the world.”

Mr.

Kelada was chatty. He talked

of New York and of San Francisco.

He discussed plays, pictures, and politics.

He was patriotic. The Union

Jack is an impressive piece of drapery, but when it is flourished by a gentleman

from Alexandria or Beirut, I cannot but feel that it loses somewhat in dignity.

Mr. Kelada was familiar.

I do not wish to put on airs, but I cannot help feeling that it is seemly in a

total stranger to put mister before my name when he addresses me. Mr.

Kelada, doubtless to set me at my ease, used no such formality. I did not like Mr. Kelada. I had

put aside the cards when he sat down, but now, thinking that for this first

occasion our conversation had lasted long enough, I went on with my game.

“The three on the four,”

said Mr. Kelada.

There is nothing more

exasperating when you are playing patience than to be told where to put the card

you have turned up before you have a chance to look for yourself.

“It’s coming out, it’s

coming out,” he cried. “The ten on

the knave.”

With rage and hatred in

my heart I finished.

Then he seized the pack.

“Do you like card

tricks?”

“No, I hate card

tricks,” I answered.

“Well, I’ll just show

you this one.”

He showed me three. Then I said I would go down to the

dining-room and get my seat at the table.

“Oh, that’s all right,”

he said, “I’ve already taken a seat for you.

I thought that as we were in the same stateroom we might just as well sit at the

same table.”

I did not like Mr. Kelada.

I not only shared a

cabin with him and ate three meals a day at the same table, but I could not walk

round the deck without his joining me.

It was impossible to snub him. It never occurred to him that he was not

wanted. He was certain that you

were as glad to see him as he was to see you.

In your own house you might have kicked him downstairs and slammed the

door in his face without the suspicion dawning on him that he was not a welcome

visitor. He was a good mixer, and

in three days knew everyone on board.

He ran everything. He managed the

sweeps, conducted the auctions, collected money for prizes at the

sports, got up quoit and golf matches, organized the concert and arranged the

fancy-dress ball. He was everywhere

and always. He was certainly the

best hated man in the ship. We

called him Mr. Know-All, even to his face. He took it as a compliment. But it was at mealtimes that he was most

intolerable. For the better part of

an hour then he had us at his mercy.

He was hearty, jovial, loquacious and argumentative. He knew everything better than anybody else, and it was an

affront to his overweening vanity that

you should disagree with him. He

would not drop a subject, however unimportant, till he had brought you round to

his way of thinking. The

possibility that he could be mistaken never occurred to him.

He was the chap who knew. We

sat at the doctor’s table. Mr. Kelada would certainly have had it all

his own way, for the doctor was lazy and I was frigidly indifferent, except for

a man called Ramsay who sat there also.

He was as dogmatic as Mr.

Kelada and resented bitterly the Levantine’s cocksureness. The discussions they had were acrimonious and interminable.

Ramsay was in the

American Consular Service and was stationed at Kobe.

He was a great heavy fellow from the Middle West, with loose fat under a tight

skin, and he bulged out of his ready-made clothes.

He was on his way back to resume his post, having been on a flying visit

to New York to fetch his wife who had been spending a year at home. Mrs.

Ramsay was a very pretty little thing, with pleasant manners and a sense

of humour. The Consular Service is

ill paid, and she was dressed always very simply; but she knew how to wear her

clothes. She achieved an effect of

quiet distinction. I should not

have paid any particular attention to her but that she possessed a quality that

may be common enough in women, but nowadays is not obvious in their demeanour. It shone in her like a flower on a coat.

One evening at dinner

the conversation by chance drifted to the subject of pearls.

There had been in the papers a good deal of talk about the cultured

pearls which the cunning Japanese were making, and the doctor remarked that they

must inevitably diminish the value of real ones. They were very good already; they would soon be perfect. Mr.

Kelada, as was his habit, rushed the new topic. He told us all that was to be known

about pearls. I do not believe

Ramsay knew anything about them at all, but he could not resist the opportunity

to have a fling at the Levantine, and in five minutes we were in the middle of a

heated argument. I had seen Mr. Kelada vehement and voluble before, but

never so voluble and vehement as now.

At last something that Ramsay said stung him, for he thumped the table

and shouted.

“Well, I ought to know

what I am talking about, I’m going to Japan just to look into this Japanese

pearl business. I’m in the trade and there’s not a man

in it who won’t tell you that what I say about pearls goes. I know all the best pearls in the world, and what I don’t

know about pearls isn’t worth knowing.”

Here was news for us,

for Mr. Kelada, with all his loquacity, had

never told anyone what his business was.

We only knew vaguely that he was going to Japan on some commercial errand. He looked around the table triumphantly.

“They’ll never be able

to get a cultured pearl that an expert like me can’t tell with half an eye.” He

pointed to a chain that Mrs. Ramsay

wore. “You take my word for it, Mrs. Ramsay, that chain you’re wearing will

never be worth a cent less than it is now.”

Mrs.

Ramsay in her modest way flushed a little and slipped the chain inside

her dress. Ramsay leaned forward. He gave us all a look and a smile

flickered in his eyes.

“That’s a pretty chain

of Mrs. Ramsay’s, isn’t it?”

“I noticed it at once,”

answered Mr. Kelada.

“Gee, I said to myself, those are pearls all right.”

“I didn’t buy it myself,

of course. I’d be interested to know how much you

think it cost.”

“Oh, in the trade

somewhere round fifteen thousand dollars.

But if it was bought on Fifth Avenue I shouldn’t be surprised to hear anything

up to thirty thousand was paid for it.”

Ramsay smiled grimly.

“You’ll be surprised to

hear that Mrs. Ramsay bought that string at a

department store the day before we left New York, for eighteen dollars.”

Mr.

Kelada flushed.

“Rot.

It’s not only real, but it’s as fine a string for its size as I’ve ever

seen.”

“Will you bet on it? I’ll bet you a hundred dollars it’s

imitation.”

“Done.”

“Oh, Elmer, you can’t

bet on a certainty,” said Mrs.

Ramsay.

She had a little smile

on her lips and her tone was gently deprecating.

“Can’t I?

If I get a chance of easy money like that I should be all sorts of a fool

not to take it.”

“But how can it be

proved?” she continued. “It’s only

my word against Mr. Kelada’s.”

“Let me look at the

chain, and if it’s imitation I’ll tell you quickly enough.

I can afford to lose a hundred dollars,” said Mr. Kelada.

“Take it off, dear. Let the gentleman look at it as much as

he wants.”

Mrs.

Ramsay hesitated a moment.

She put her hands to the clasp.

“I can’t undo it,” she

said, “Mr. Kelada will just have to take my word

for it.”

I had a sudden suspicion

that something unfortunate was about to occur, but I could think of nothing to

say.

Ramsay jumped up.

“I’ll undo it.”

He handed the chain to

Mr. Kelada.

The Levantine took a magnifying glass from his pocket and closely

examined it. A smile of triumph

spread over his smooth and swarthy face.

He handed back the chain. He was

about to speak. Suddenly he caught

sight of Mrs. Ramsay’s face. It was so white that she looked as though she were about to

faint. She was staring at him with

wide and terrified eyes. They held

a desperate appeal; it was so clear that I wondered why her husband did not see

it.

Mr.

Kelada stopped with his mouth open.

He flushed deeply. You could

almost see the effort he was making over himself.

“I was mistaken,” he

said. “It’s very good imitation, but of course

as soon as I looked through my glass I saw that it wasn’t real. I think eighteen dollars is just about

as much as the damned thing’s worth.”

He took out his

pocketbook and from it a hundred dollar note.

He handed it to Ramsay without a word.

“Perhaps that’ll teach

you not to be so cocksure another time, my young friend,” said Ramsay as he took

the note.

I noticed that Mr. Kelada’s hands were trembling.

The story spread over

the ship as stories do, and he had to put up with a good deal of chaff that

evening. It was a fine joke that Mr. Know-All had been caught out. But Mrs.

Ramsay retired to her stateroom with a headache.

Next morning I got up

and began to shave. Mr. Kelada lay on his bed smoking a cigarette. Suddenly there was a small scraping

sound and I saw a letter pushed under the door.

I opened the door and looked out.

There was nobody there. I

picked up the letter and saw it was addressed to Max Kelada. The name was written in block letters. I handed it to him.

“Who’s this from?” He

opened it. “Oh!”

He took out of the

envelope, not a letter, but a hundred-dollar note.

He looked at me and again he reddened.

He tore the envelope into little bits and gave them to me.

“Do you mind just

throwing them out of the porthole?”

I did as he asked, and

then I looked at him with a smile.

“No one likes being made

to look a perfect damned fool,” he said.

“Were the pearls real?”

“If I had a pretty

little wife I shouldn’t let her spend a year in New York while I stayed at

Kobe,” said he.

At that moment I did not

entirely dislike Mr. Kelada. He reached out for his pocketbook and carefully put in it the

hundred-dollar note.

9

Keeping Errors at Bay

Bertrand Russell (England, 1872-1970)

o avoid the various foolish opinions to

which mankind are prone, no superhuman genius is required. A few simple rules will keep you, not

from all error, but from silly error.

o avoid the various foolish opinions to

which mankind are prone, no superhuman genius is required. A few simple rules will keep you, not

from all error, but from silly error.

If

the matter is one that can be settled by observation, make the observation

yourself. Aristotle could have

avoided the mistake of thinking that women have fewer teeth than men by the simple device of asking Mrs. Aristotle to

keep her mouth open while he counted.

He did not do so because he thought he knew.

Thinking that you know when in fact you don't is a fatal mistake, to

which we are all prone. I believe

myself that hedgehogs eat black beetles, because I have been told that they do;

but if I were writing a book on the habits of hedgehogs, I should not commit

myself until I had seen one enjoying this unappetizing diet. Aristotle, however, was less cautious. Ancient and medieval authors knew all

about unicorns and salamanders; not one of them thought it necessary to avoid

dogmatic statements about them because he had never seen one of them.

Many matters, however, are less easily

brought to the test of experience.

If, like most of mankind, you have passionate convictions on many such matters,

there are ways in which you can make yourself aware of your own bias. If an opinion contrary to your own makes

you angry, that is a sign that you are subconsciously aware of having no good

reason for thinking as you do. If

someone maintains that two and two are five, or that Iceland is on the equator,

you feel pity rather than anger, unless you know so little of arithmetic or

geography that his opinion shakes your own contrary conviction. The most savage controversies are those

about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way. Persecution is used in theology, not in

arithmetic, because in arithmetic there is knowledge, but in theology there is

only opinion. So whenever you find

yourself getting angry about a difference of opinion, be on your guard; you will

probably find, on examination, that your belief is going beyond what the

evidence warrants.

A good way of ridding yourself of

certain kinds of dogmatism is to become aware of opinions held in social circles

different from your own. When I was

young, I lived much outside my own country—in France, Germany, Italy, and the

United States. I found this very

profitable in diminishing the intensity of insular prejudice. If you cannot travel, seek out people

with whom you disagree, and read a newspaper belonging to a party that is not

yours. If the people and the

newspaper seem mad, perverse, and wicked, remind yourself that you seem so to

them. In this opinion both parties may be

right, but they cannot both be wrong.

This reflection should generate a certain caution.

Becoming aware of foreign customs,

however, does not always have a beneficial effect. In the seventeenth century, when the Manchus conquered China,

it was the custom among the Chinese for the women to have small feet, and among

the Manchus for the men to wear pigtails.

Instead of each dropping their own foolish custom, they each adopted the

foolish custom of the other, and the Chinese continued to wear pigtails until

they shook off the dominion of the Manchus in the revolution of 1911.

For

those who have enough psychological imagination, it is a good plan to imagine an

argument with a person having a different bias. This has one advantage, and only one, as compared with actual

conversation with opponents; this one advantage is that the method is not

subject to the same limitations of time and space. Mahatma Gandhi deplored railways and steamboats and

machinery; he would have liked to undo the whole of the industrial revolution. You may never have an opportunity of

actually meeting anyone who holds this opinion, because in Western countries

most people take the advantage of modern technique for granted. But if you want to make sure that you

are right in agreeing with the prevailing opinion, you will find it a good plan

to test the arguments that occur to you by considering what Gandhi might have

said in refutation of them. I have

sometimes been led actually to change my mind as a result of this kind of

imaginary dialogue, and, short of this, I have frequently found myself growing

less dogmatic and cocksure through realizing the possible reasonableness of a

hypothetical opponent.

Be very wary of opinions that flatter your self‑esteem. Both men and women, nine times out of

ten, are firmly convinced of the superior excellence of their own sex. There is abundant evidence on both

sides. If you are a man, you can point out that

most poets and men of science are male; if you are a woman, you can retort that

so are most criminals. The question

is inherently insoluble, but self‑esteem conceals this from most people.

We are all, whatever part of the world we come from, persuaded that our own

nation is superior to all others.

Seeing that each nation has its characteristic merits and demerits, we adjust

our standard of values so as to make out that the merits possessed by our nation

are the really important ones, while its demerits are comparatively trivial.

Here, again, the rational man will admit that the question is one to

which there is no demonstrably right answer.

It is more difficult to deal with the self‑esteem of man as man, because

we cannot argue out the matter with some non‑human mind. The only way I know of dealing with this

general human conceit is to remind ourselves that man is a brief episode in the

life of a small planet in a little corner of the universe, and that, for aught

we know, other parts of the cosmos may contain beings as superior to ourselves

as we are to jelly‑fish.

Other passions besides self‑esteem are common sources of error; of these perhaps

the most important is fear.

Fear sometimes operates directly, by inventing rumours of disaster in

war‑time, or by imagining objects of terror, such as ghosts; sometimes it

operates indirectly, by creating belief in something comforting, such as the

elixir of life, or heaven for ourselves and hell for our enemies. Fear has many forms—fear of death, fear

of the dark, fear of the unknown, fear of the herd, and that vague generalized

fear that comes to those who conceal from themselves their more specific

terrors. Until you have admitted

your own fears to yourself, and have guarded yourself by a difficult effort of

will against their myth‑making power, you cannot hope to think truly about many

matters of great importance, especially those with which religious beliefs are

concerned. Fear is the main source

of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of

wisdom, in the pursuit of truth as in the endeavour after a worthy manner of

life.

9

Nine Puzzles

A jeweler has 3

diamonds. They all look exactly

alike, but one diamond is heavier than the others. How can she identify the heavier diamond by using a balance

scale just once? Please outline

your argument as carefully as you can.

2. Same as above, but

now the jeweler doesn’t know whether the odd diamond is lighter or heavier than

the other two. By using the scale

twice, how can she tell (i) which is the odd one, and (ii) whether it is lighter

or heavier?

3. What do you see in

the following two sketches?

4. One morning, exactly at sunrise, a Buddhist monk began to

climb a tall mountain. The narrow

path, no more than a foot or two wide, spiraled around the mountain to a

glittering temple at the summit.

The monk ascended the path at varying rates of speed, stopping many times along

the way to rest and to eat the dried fruit he carried with him.

He reached the temple shortly before sunset. After several days of fasting and meditation he began his

journey back along the same path, starting at sunrise and again walking at

variable speeds with many pauses along the way.

His average speed descending was, of course, greater than his average

climbing speed. Prove that there is

a spot along the path that the monk will occupy on both trips at precisely the

same time of day.

4. One morning, exactly at sunrise, a Buddhist monk began to

climb a tall mountain. The narrow

path, no more than a foot or two wide, spiraled around the mountain to a

glittering temple at the summit.

The monk ascended the path at varying rates of speed, stopping many times along

the way to rest and to eat the dried fruit he carried with him.

He reached the temple shortly before sunset. After several days of fasting and meditation he began his

journey back along the same path, starting at sunrise and again walking at

variable speeds with many pauses along the way.

His average speed descending was, of course, greater than his average

climbing speed. Prove that there is

a spot along the path that the monk will occupy on both trips at precisely the

same time of day.

5. Three glasses

contain liquid, and three are empty.

Rearrange the glasses so that they alternate—one with liquid, one

without, one with liquid, one without, etc.

You are allowed to touch or move only one glass.

6. In her drawer, Cathy has six pairs of black gloves and six pairs of brown

gloves . In complete darkness, how many gloves must she take from the drawer in

order to be sure to get a matching pair?

Think carefully!!

7. Cigars cannot be smoked all the way to the end, so most cigar smokers

generate and discard butts. A poor

man can make one cigar from every 5 discarded cigar butts he collects. Today, he

collected 25 butts. How many cigars will he be able to smoke?

8. To tackle this

problem, imagine yourself a raven.

You can still reason as well (or as badly?J)

as you always do, but you have the body of a raven. You are starving, and ravens do love meat. There is a fine chunk of salami about 3

feet below you, tied to a string.

The other side of the string is securely tied to your perch. By now, you have unsuccessfully tried the following:

q Bending down as

far as you can, grabbing the string with your bill and lifting it up--but it was

too long and it still dangled down below you.

q Grabbing the

salami chunk while flying, jumping upwards from the ground, or falling down from

the perch.

q Tearing or

untying the string.

q Breaking the

perch.

q Climbing down

the string (ravens, you found out, can’t do that sort of thing).

q Swinging the

string upwards towards you.

q Coiling the

string repeatedly around your perch.

And yet, that salami

down there smells so very good!

What are you going to do??? (For an online hint, and to see how elephants solved

this program, go to:

http://youtube.com/watch?v=rplLLmx5xtY)

9. Tower of Hanoi Puzzle

9. Imagine that you are faced with a board that has 3 pegs, I, II, and III (see

the figure above). Peg I has 3

disks of different sizes, with the largest disk, G(reen), at the bottom, the

middle one, R(ed), in the middle, and the smallest one, B(lue), on top. You need to transfer all 3 disks to peg

III, as shown in the figure below—this is you goal state. In doing so, you must follow five rules:

1.

You can only move one disk at a time.

2. A disk must be moved from one peg to

another.

3.

You can only move the top disk of a peg (e.g., in the first figure above, you

can only move Disk B of Peg I to either Peg II or Peg III).

4. A disk cannot be placed on a disk

smaller than itself (e.g., Disk R can never be placed on top of Disk B).

5. Number of allowed steps: 7 or less.

Write a

step-by-step

solution to this problem, so that a dumb robot might be able to follow your

instructions.

Step 1.

Step 2.

Step 3.

Step 4.

Step 5.

Step 6.

Step 7.

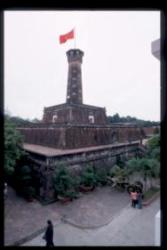

Photo: The real tower of Hanoi

9

WHAT IS INTELLIGENCE, ANYWAY?

Isaac Asimov (USA, 1920-1992)

hat is intelligence, anyway? When I was in the

army, I received the kind of aptitude test that all soldiers took and, against a

normal of 100, scored 160. No one

at the base had ever seen a figure like that, and for two hours they made a big

fuss over me. (It didn’t mean

anything. The next day I was still

a buck private with KP—kitchen police—as my highest duty.)

All my life I’ve been registering scores like that, so that I have the

complacent feeling that I’m highly intelligent, and I expect other people to

think so, too. Actually, though,

don’t such scores simply mean that I am very good at answering the type of

academic questions that are considered worthy of answers by people who make up

the intelligence tests—people with intellectual bents similar to mine?

For instance, I had an auto-repair man once, who, on these intelligence tests,

could not possibly have scored more than 80, by my estimate. I always took it for granted that I was

far more intelligent than he was.

Yet, when anything went wrong with my car I hastened to him with it, watched him

anxiously as he explored its vitals, and listened to his pronouncements as

though they were divine oracles—and he always fixed my car.

Well, then, suppose my auto-repair man devised questions for an intelligence

test. Or suppose a carpenter did,

or a farmer, or, indeed, almost anyone but an academician. By every one of those tests, I’d prove myself a moron. And, I’d be a moron, too. In a world where I could not use my

academic training and my verbal talents but had to do something intricate or

hard, working with my hands, I would do poorly.

My intelligence, then, is not absolute but is a function of the society I

live in and of the fact that a small subsection of that society has managed to

foist itself on the rest as an arbiter of such matters.

Consider my auto-repair man, again.

He had a habit of telling me jokes whenever he saw me.

One time he raised his head from under the automobile hood to say: “Doc,

a deaf-and-mute guy went into a hardware store to ask for some nails. He put two fingers together on the

counter and made hammering motions with the other hand. The clerk brought him a hammer.

He shook his head and pointed to the two fingers he was hammering. The clerk brought him nails. He picked out the sizes he wanted, and

left. Well, Doc, the next guy who

came in was a blind man. He wanted

scissors.

How do you suppose he asked for them?”

Indulgently, I lifted my right hand and made scissoring motions with my first

two fingers. Whereupon my

auto-repair man laughed raucously and said, “Why, you dumb jerk, he used his

voice and asked for them.” Then he

said smugly, “I’ve been trying that on all my customers today.”

“Did you catch many? I asked.

“Quite a few,” he said, “but I knew for sure I’d catch you.” “Why is that?” I asked. “Because you’re so goddamned educated,

Doc, I knew you couldn’t be very smart.”

And I have an uneasy feeling he had something there.

9

Lesson 28

1. Read pp. **

("The Stub Book").

2. Pedro Antonio

de Alarcón (1833-1891) was a Spanish writer and diplomat.

3. Please re-tell

“The Stub Book” in one short paragraph.

4. Is it possible

for a man to love his pumpkins, view them as “the daughters of his toil,” and

grieve when he has to bid them adios?

5. When did the idea of cutting the stems occur to Uncle Buscabeatas? What decisive step did he take before

leaving for the market town of

Cádiz? Why are we only told that he “lingered

for some twenty minutes at the scene of the catastrophe” but are only told later

what actually transpired in those twenty minutes?

6. What was the

source of Uncle Buscabeatas’s

brilliant idea of cutting the stems of the stolen pumpkins and bringing them to

Cádiz? Could we say that sometimes great

discoveries are based on the same principle, e.g., making a great discovery in

the discipline of astronomy by relying on ideas from the discipline of

mathematics?

7. The story ends with a much-deserved victory for Uncle Buscabeatas. But wait: Couldn’t Uncle Fulano claim

that Buscabeatas stole the stems

from Fulano’s field?

8. Are there similarities in the way Uncle Buscabeatas solved the

mystery of the missing pumpkins and the way Dr. Semmelweis (pp. *) solved the mystery of the

dying mothers? Did one of these

solutions require greater imagination and creativity than the other? If not, could we say that most of us,

given the right circumstances, have the potential of making great cultural

contributions?

Follow-up Reading and Viewing for Pleasure

Pedro Antonio de Alarcón

. 1974.

The Three-Cornered Hat (a touching comedy based in Alarcón native

Andalusia).

Lesson 29

1. Read pp.

225‑32 ("Mr. Know‑All").

2. Listen to a short story on Tape or

CD: "Mr. Know‑All."

3.

A Rashomon Effect Exercise: Briefly retell the story, not from Mr. Maugham's

viewpoint, but from Mr. Kelada's.

In retelling this story, assume that, although he was perfectly aware of his

fellow passengers' prejudices, Mr. Kelada chose to ignore them.

4. Read the Spotlight below

("Conversations with a Critical Thinker") and answer questions a‑e.

|

Conversations

with a

Critical

Thinker

(OR: Black on

White = Right)

The first draft of

Adventures in English placed Maugham's "Mr.

Know‑All" in the "Crosscultural

Bridges" unit.

After all, the story involved Americans, Englishmen, and a Middle

Easterner who is, according to the narrator of the story, trying to pass as

an Englishman.

But just then,

an Egyptian scholar visited the Central Department of English.

Now "Mustafa" liked our book and was contemplating its adoption in his

native land, until he noticed "Mr. Know‑All." At that moment, all hell broke loose.

"What's the

matter, Mustafa?" one of us asked.

"My dear Nepali

colleagues," he began. "I am

truly astonished that you chose to include this piece of 'literature' in

your collection."

"Why?" we asked,

taken aback by astonishment.

"Well," Mustafa

said, "I feel that you have unknowingly succumbed to Mr. Maugham's superb

storytelling gift, and that you have ignored a most disturbing aspect of his

story."

)

We were still

puzzled, and said so. So Mustafa continued.

"My esteemed

friends, Mr. Maugham is an out‑and‑out racist.

Read the story with this new allegation in mind, and judge for

yourselves."

We did, and

found Mustafa's charge of racism not as absurd as it first appeared.

So we hastily transferred the story from the "Crosscultural

Bridges" to the "Critical and Creative Thinking" unit of Adventures in English. And, before we continue, we would like

you to convince yourself that Mustafa's accusation is sensible:

a. Please re‑read the story (pp. 225‑32) and cite at least three instances which

seem to document Mustafa's claim of racism (the answer to this question

appears in Appendix XIII, p. 386).

b. State whether, in your opinion, Somerset

Maugham shares the view that "there is only one caste, the caste of

humanity?"

At this point, however, one of us interrupted Mustafa and argued that his

accusation rested on a misconception.

That is, Mustafa seemed to have confused the person who tells the story

with Mr. Maugham. The narrator,

perhaps, looks down on Egyptians and Nepalis, but he should not be confused

with Mr. Maugham.

Mustafa was

equal to this task. He reminded us that we had never been

under direct English occupation, while Egyptians had experienced British

condescension first hand. He

argued that Maugham never took the trouble to distance himself from the

narrator. Finally, he marshaled a few other

illustrations of Maugham's parochialism.

For instance, he reminded us of Maugham's "Alien Corn," which again

capitalizes, patronizingly, on ethnic differences. And this leads us to the next

assignment:

c. In a single paragraph, please comment on

Mustafa's argument: Is he right

in insisting that Maugham himself is a racist?

You would think

by now that old Mustafa had made his point, and that he would join us for

some long‑overdue tiffin at the

Kathmandu Coffee House. But our hopes were quickly dashed, for

at this point Mustafa turned his critical gaze on another aspect of "Mr.

Know‑All."

"My esteemed

Nepali colleagues," Mustafa proceeded, "I can understand how Maugham's

ethnocentricity escaped you, but what really baffles me is that you failed,

as well, to notice his shoddy math.

In fact, even if Maugham was a honest man (which I doubt), I wouldn't

trust him with giving me correct change for a fifty‑rupee note. I sense, however, that you are all

anxious to savor some Masala Dosa and coconut chutney, and I must confess that I myself would love to

sample a few South Indian dishes.

So let us drop this subject for the moment.

When you go home tonight, I urge you to re‑read Maugham's captivating

story once more and convince yourselves that I am right."

So we did go to

lunch. And then, at Mustafa's insistence, we

went to Thamel Market, and saw Mustafa in action (in addition to being a

critical thinking ace, he is, no doubt, the best bargainer this side of the

Indian Ocean). We then went

home, re‑read the story, and saw that indeed Mr. Maugham committed an

embarrassing mathematical error.

d. Explain Maugham's error? (the answer to this question appears in Appendix XIII, p. 386).

When we got

together again, one of us said:

"Sure, the

mathematical error is there, but this does not mean that Mr. Maugham is a

careless mathematician. The

error, rather, is committed by one character of the story, not by Mr.

Maugham. "Mr. Know‑All," for all we know, might

be nothing more than a faithful rendition of an actual event in Mr.

Maugham's life."

e. We

shall not reproduce Mustafa's reply to this question. Instead, we shall ask you to provide

your own answer. So, what do

you think, is Mr. Maugham guilty of bad math, or did he deliberately include

this error in the story? Please

explain your answer.

|

Reading for Pleasure

Other celebrated Somerset Maugham's stories include "Rain," "The Kite," and "The

Verger."

His best novel is perhaps The

Razor's Edge.

Lesson 30

1. Read pp. *

("What is Intelligence, Anyway?").

2. Try to solve the creative thinking

puzzles on pp. 237‑40 (answers to these puzzles

appear in Appendix XII, pp.

3. Please prepare a brief class

presentation (less than five minutes long) on the topic: "For me, the most

interesting point in Asimov's essay (pp. 233‑6)

is [describe, explain, and illustrate this point] because [explain your reasons

for thinking it most interesting]."

4. Do you agree with Asimov that human beings cannot be placed on a

one-dimensional intelligence scale, that they are all made up of a unique

mixture of intelligence and stupidity?

5. Try telling

Asimov’s joke to a couple of friends.

Did they fall into the same trap that Asimov fell into, or were they more

“intelligent” than he was.

6. The

so-called “intelligence test” has often been used to label and exclude people.

For instance, in the USA in the 1920s, the test was used to justify

discrimination against Italians Russians, Jews, Poles . . .

Asimov’s parents were almost certainly excluded from polite society because of

their poverty, foreign accents, and Eastern-European origins.

Do you think such personal experiences might have contributed to Asimov’s

skeptical views of official I.Q. tests—despite the fact that he himself scored

very high in these very tests?

4. In small groups, please edit Sentences 60‑79 of Appendix III (pp. **). When done, compare your answers to those

given in Appendix IV (pp. **).

Reading for Pleasure

Asimov, Isaac. 1972.

The Gods Themselves (a great science fiction novel).

POSTSCRIPT

You can have all the virtues—that's to say, all except the two that really

matter, understanding and compassion—you can have all the others, I say, and be

a thoroughly bad man.

Aldous Huxley

Ekta Books

/

Flax-Golden

Tales-Sounds of English

/ Moti Nissani’s Homepage