Interdisciplinary Journeys

Keynote address at the December 2016 conference of the Sri Lankan Association for the Advancement of Science

Acknowledgment: Before embarking on our interdisciplinary journey, I want to thank SLAAP for inviting me. Words, especially, cannot describe my feelings of gratitude to Dr. Manjula Vidanapathirana, for the stimulating conversations the two of us had about this presentation and the conference as a whole, and for taking care of so many technical details that our trip to your island involved. Above all, I want to thank her for writing this to me, after I sent her my paper: “I just can't believe that I found a colleague who can create such an intellectual turbulence.” I likewise can’t believe that I found colleague who, in the true spirit of truth-seeking, actually welcomes turbulence.

So put on your life vests and let’s begin our brief journey.

In 1997, my university department officially became “the Interdisciplinary Studies Program.” Perhaps because I was the only faculty member who had degrees in genetics (natural sciences), psychology (social sciences), and philosophy (humanities), and because by then I taught almost every course in our general studies curriculum, I was asked to teach a course that would serve as an introduction to the field of interdisciplinary studies.

Shortly thereafter, I realized that I was an interdisciplinarian in the first sense of the word, but not in its second sense.

The sense that applied to me was a commitment to holistic thinking, teaching, and research.

Until then, however, I hadn’t given much thought to the second, reflexive, sense of interdisciplinarity. That is, I was never concerned with interdisciplinary theory: What interdisciplinarity is, where you can find it, how you can rank different interdisciplinary endeavors, and what it is good for.

I had an entire summer to prepare for that course, and so I started reading intensively about interdisciplinary theory, trying to assemble a coursepack for my students. To my regret, I soon realized that almost everything I read was merely an attempt to create yet another academic discipline: that of studying interdisciplinarity. It seemed to me that most such writings about interdisciplinarity did not throw much light on the subject, and that they in fact diverted attention from the only thing about interdisciplinarity that really mattered to me: Understanding reality as a whole.

So I ended up writing a couple of papers on the subject of interdisciplinary theory for my students, which, I felt, was everything that anyone needed to know about the subject. We read those papers, took a brief look at what interdisciplinarity was, and spent most of the time exploring and illustrating the power of interdisciplinarity in action.

And that is what I’d like to do in this address: Briefly review all you need to know, in my view, about interdisciplinary theory, and then showcase the enormous power of interdisciplinary practice.

What is Interdisciplinarity and Where do you Find it?

Interdisciplinary theorists tend to needlessly confuse their audience by talking about such things as crossdisciplinarity, transdisciplinarity, pluridisciplinarity, and multidisciplinarity. In my view, there is nothing to gain from such terms. Instead, I’d like to provide a simple definition of interdisciplinarity.[1]

To begin with, a discipline can be conveniently defined as any comparatively self-contained and isolated domain of human experience which possesses its own community of experts, e.g., music, physics. With time, such broad disciplines maybe subdivided, e.g., classical music, nuclear physics.

Interdisciplinarity is best seen as bringing together distinctive components of two or more disciplines.

In academic discourse, interdisciplinarity typically applies to four realms: knowledge, cultural innovations (e.g., scientific research, writing novels), education, and theory.

Interdisciplinary knowledge involves familiarity with components of two or more disciplines. In that sense, you are an interdisciplinarian if you know that 2+2=4 (math) and that water is H2O (chemistry). So we are all interdisciplinarians.

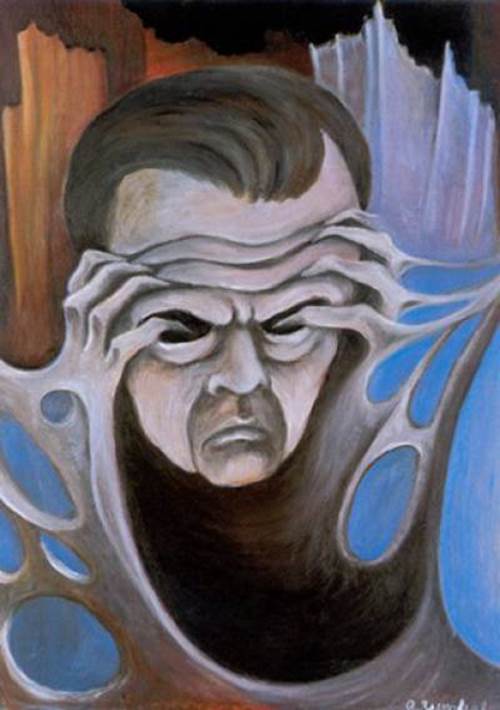

Interdisciplinary cultural innovations combine components of two or more disciplines in the search or creation of new knowledge, operations, or artistic expressions. For instance, consider this painting:

<Painting caption: Alexander Zinoviev’s Self-Portrait: Thinking is Painful: “Striving after the painful truth has become the fate of exceptionally rare loners.”>

Clearly, this painting involves interdisciplinary research: It is an artistic creation involving insights from psychology (most people shun ugly truths) and politics (the realization that there is a great deal of needless ugliness in our world).

Interdisciplinary education merges components of two or more disciplines in a single program of instruction; for instance, I once taught a course on science and religion.

Interdisciplinary theory, as we have seen, takes interdisciplinary knowledge, research, or education as its main objects of study. This part of my talk is an example of interdisciplinary theory.

How do you Rank Interdisciplinary Undertakings?

Although we are all interdisciplinarians, we need criteria to distinguish between, e.g.:

· An 8-year-old who knows that Sri Lanka is an island (geography) and that water is a compound (chemistry),

and

· An Albert Einstein who made major contributions to both physics and politics.

The interdisciplinary richness[2] of any two instances of knowledge, innovation, or education can be ranked by weighing four variables: number of disciplines involved, the "distance" between them, the novelty of any particular combination, and their extent of integration.

You can either eat mangos, or bananas, or papayas singly. Or you can eat 2 at the same time, or 3. You can eat all 3, and add a tomato to the mixture (more distant). You can chop them into a fruit salad, or you can blend them all into a smoothie. The same idea can be used to rank interdisciplinary undertakings.

Take interdisciplinary research (cultural innovation) as one example of such a continuum. A scholar might specialize in only one sub-field of mathematics, two-subfields, mathematics and physics (the number of disciplines went from one to two), mathematics and literature (the number remained the same but they are more distant from each other and they are not often brought together in the same research program), mathematics, literature, and linguistics (the number of disciplines is higher and this combination has a higher degree of novelty), or she might weave her knowledge of the last three into essential components of the same research project (higher extent of integration).

More generally, one might be concerned primarily with one's own discipline; one might occasionally incorporate in one's mind, creative undertakings, or teaching some limited insights or methodologies from another field; or one might be a true Renaissance Scholar, not only at home in a number of distant areas in the arts, sciences, and humanities, but in a position to creatively integrate them in one's mind, research, or teaching.

Advantages of Interdisciplinarity

There are many reasons why we should move in an interdisciplinary direction in our studies, research, and teaching—and there is, as well, a price to pay for taking this road. Here I’d just like to highlight a few reasons for moving in that direction ourselves, or, at the very least, becoming part of a multidisciplinary team.

Among the many advantages of interdisciplinarity, I’d like to briefly mention four and then spend the rest of this address on two additional ones.

Interdisciplinary knowledge and research are important because:

1. Creativity often Requires Interdisciplinary Knowledge

Example: Gregor Mendel relied on his knowledge of statistics to explain his path-breaking results with the garden pea.

2. Immigrants often make Important Contributions to their New Field

Example: In the 1950s-1970s molecular biology had been transformed by mass migration of physicists into the field.

3. Disciplinarians often Commit Errors which can be Best Detected by People well-versed in two or more Disciplines

For instance, the Hardy-Weinberg law in genetics owes its origins to a mathematician, Hardy, noticing a mathematical error in a paper by a renowned biologist.

4. Interdisciplinary Knowledge and Innovation Serve to Remind us of the Unity-of-Knowledge Ideal

There is something incongruous in a person resigning herself to knowing one thing very well and giving up on her efforts to understand reality as a whole. This commitment to specialization diminishes us as scholars and human beings:

Previously, men could be divided simply into the learned and the ignorant, those more or less the one, and those more or less the other. But your specialist cannot be brought in under either of these two categories. He is not learned, for he is formally ignorant of all that does not enter into his specialty; but neither is he ignorant, because he is "a scientist," and "knows" very well his own tiny portion of the universe. We shall have to say that he is a learned ignoramus, which is a very serious matter, as it implies that he is a person who is ignorant, not in the fashion of the ignorant man, but with all the petulance of one who is learned in his own special line.[3]

The reverse of this is the true interdisciplinarians. Many of the most interesting minds of the previous century were exactly that: Mohandas Gandhi, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, Aldous Huxley, Karl Popper. Such people share one characteristic: They tried to see the whole orchard, not just one leaf of one tree.

5. Many Intellectual, Social, and Practical Problems Require Interdisciplinary Approaches

To illustrate this advantage, let us look at one subject of grave concern to our species: Climate change.

You can only begin to understand climate change holistically. Here are some of the disciplines that must be relied on to comprehend this complex problem:

· Engineering. We can make cars that are at least 4 times as efficient as contemporary cars, thereby saving our money, health, and future.

· Politics, e.g., All countries of the world ban a 4X improvement in gasoline efficiencies because they are all ruled, behind the scenes, by bankers and oilmen. What will happen to the bottom line of British Petroleum if you could drive six times from Colombo to Kandy and back without once filling your gas tank?

· Chemistry, e.g., properties of CO2, CH4, and other greenhouse gases.

· Atmospheric science, e.g., what is the impact of ever more greenhouse gases on air circulation?

· Oceanography, e.g, impact of warming on ocean acidification.

· Computer science, e.g. using modeling and the tremendous calculating power of computers to project the impact of rising concentrations of greenhouse gases on such a complex system as planet earth.

· Ecology, e.g., the impact of rising temperatures on biodiversity.

· Health, e.g., impact of rising temperature on the distribution of disease vectors.

· Geography, e.g., obviously, low-lying Colombo is at greater risk of rising sea levels than the hills of central Sri Lanka.

· Politics, Psychology, history, biology, e.g., some people predict catastrophe. Why is nothing being done?

· Politics, e.g., absence of real democracy; sunshine bribery, frequent assassinations[4] of environmental activists.

Obviously, it all boils down to this: The only people who can truly understand climate change are truth-seekers who have no respect for interdisciplinary boundaries. And: The people who benefit in the short-term from climate change rely in part on the fact that most scholars dare not cross disciplinary boundaries.

Let me also note in passing that such a holistic understanding has personal implications too: I wouldn’t buy any low-lying real estate on the Sri Lankan coast. If I had such real estate, I’d find me an Exxon CEO and sell it to him as fast as I could.

According to one site,[5] for instance,

“It would actually take a sea level rise of 8m for coastal Sri Lanka to be literally ` underwater, but a projected range of 0.2 – 0.6m would still wreak havoc.

What you can broadly see is Negombo – at the top of the lagoon – basically going underwater pretty soon. Negombo is about 2m above sea level but the landscape is a mix of canals and lagoons, basically water woven throughout the city. . . .

Finally Colombo. The coastline here gets encroached on everywhere, though not catastrophically. We would still have to invest in sea-walling and rather expensive technology to preserve Marine Drive and the main rail line. The Port itself will be impacted, and it looks like the Beira will get an influx of sea water. It seems like sea level rise would affect waters all the way up to Nugegoda.

The need to study issues holistically applies to most major challenges that are now confronting our species: poverty, mal-distribution of wealth, a broken justice system, wars, erosion of personal freedoms, decline in educational standards, the impact of British imperial strategies on sectarian tensions in Sri Lanka, and many others.

6. Interdisciplinarity can Turn our Belief System Upside Down

The last advantage of interdisciplinarity I’d like to touch upon is its thoroughly subversive nature: It can, if you let it, revolutionize your worldview. Here are a few illustrations:

Democracy

You might think that India, the USA, or Sri Lanka, are democracies.

But if you study history, political science, the Greek language, and cultural anthropology, you will know that democracy means people power, a system where there are no professional politicians or judges. The people are in charge. I shall have a lot more to say about this in my presentation on the same topic.[6] Here I just wanted to show, again, that interdisciplinarity, if practiced, will upend most people’s conception of democracy.

Our View of the World

Most people rely on the media for their worldview. They watch CNN, or Fox, or Bollywood, or Sirasa TV, never realizing that these outlets are not concerned with truth or art but with advancing the interests of a few trillionaires.

Here is one point of origin of this tragic state of affairs. In 1917, Congressman Oscar Callaway explained how a few oligarchs colonized our minds:

In March, 1915, the J.P. Morgan interests, the steel, shipbuilding, and powder interest, and their subsidiary organizations, got together 12 men high up in the newspaper world and employed them to select the most influential newspapers in the United States and sufficient number of them to control, generally, the policy of the daily press. . . . They found it was only necessary to purchase the control of 25 of the greatest papers. An agreement was reached; the policy of the papers was bought, to be paid for by the month; an editor was furnished for each paper to properly supervise and edit information regarding the questions of preparedness, militarism, financial policies, and other things of national and international nature considered vital to the interests of the purchasers.

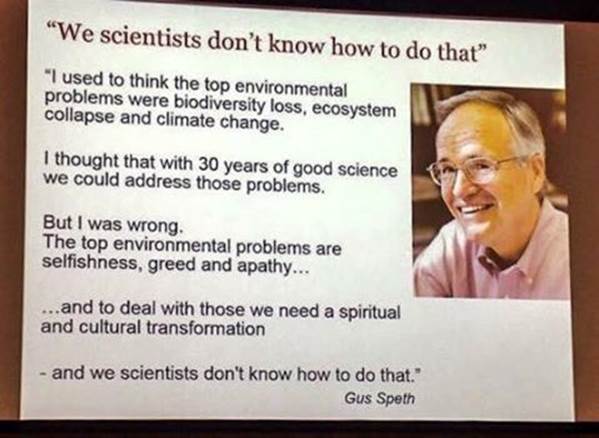

Experts

We are likewise taught to revere experts. But who are the experts, really? Should we believe the (well-paid) pundits who scoff at climate change? Should we believe the thousands of experts who aver that we should take money from poor people and hand it over to billionaires (this is happening right now in most corners of the world)? Should we use their term for robbing the poor (austerity)? Should we believe American economists who say that international bankers should not be prosecuted if they break the law?[7]

Interdisciplinarity again tell us that experts are hired, promoted, and fired, in part, on the basis of conformity to organizational discipline and goals. The consequences are predictable:

Prof. David Collingridge:

The traditional view of expert opinion is . . . radically mistaken. An expert is traditionally seen as neutral, disinterested, unbiased. . . . On the view proposed here . . . an expert is best seen as a committed advocate. . . . It is notorious that the opinion of an expert . . . can often be predicted from knowledge of which group has his affiliation.[8]

Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer:

Party interests are vehemently agitating the pens of so many pure lovers of wisdom. . . . Truth is certainly the last thing they have in mind. . . . Philosophy is misused, from the side of the state as a tool, from the other side as a means of gain. . . . Who can really believe that truth also will thereby come to light, just as a by-product? . . . Governments make of philosophy a means of serving their state interests, and scholars make of it a trade.[9]

Politician Dwight Eisenhower:

In . . . the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas . . . a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. . . . The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present-and is gravely to be regarded.[10]

Information is power; trillionaires distort reality to increase their power over us.

Personal implications. Brainwashing is like Cyanide: The only way to avoid poisoning is to avoid exposure. For instance, there is no point listening to what “experts” linked to the pesticide industry have to say about the chronic kidney disease epidemic in hot agrochemical regions of Sri Lanka[11] and Central America. So, if the truth is important to you, you should stop watching Hollywood films and the BBC. Stop reading mainstream newspapers, start discounting the views of compromised experts, and expose yourself to alternative views. Look for competence, but not from people whose task it is to confuse and make you act against your interests and convictions.

And, your best protection of course is becoming an interdisciplinarian: It’s hard to mislead people who dare study a subject in all its complexity.

Subversive Example 3:.

Most people believe that they are rational and compassionate and that they think for themselves. A cursory, cross-interdisciplinary, look strongly suggests that they are mistaken.

Psychology, history, and literature tell us about something called belief perseverance: Once we acquire a conviction, we stick to it, even when faced with overwhelming evidence against it.[12]

History and psychology again suggest that we tend to obey malevolent authority when we shouldn’t.[13]

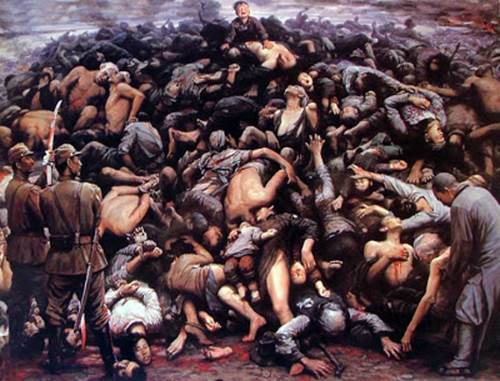

History and psychology again point to the common predisposition to excessive cruelty. Here is a painting, for instance, of the Nanjing Massacre—and history is full of such incidents of needless cruelty.

<Painting caption: Zi Jian Li's The Great Nanjing Massacre>

Personal implications: We can, if we want, achieve the Buddhist ideal of compassion and rationality. But we can only do so through a constant, conscious, struggle.

Climate Change Again

Some people, not realizing the chokehold that bankers and oilmen have on our information sources, believe that global warming is a hoax. Others, paying attention to what the majority of world’s scientists say, are convinced that global warming is a fact.

The holistic truth is that, when it comes to making predictions about something as complex as the entire planet, we can only make probability statements. In this case, most independent scientists would say that the chance that humanity is already running, or going to run into, serious problems before 2050 is over 95%.

Here the controversy ends, for a 95% probability of severe negative impacts (or even 5%) certainly requires urgent actions to avert catastrophe: Do we really want to risk the submergence of the Maldives or Colombo? Do we really want to risk a runaway heating of the planet, ending in temperatures that would bring life on earth to an end?[14]

Now, here is another disciplinary smokescreen. Even the people who recognize the urgency have been led to believe that a solution would involve enormous sacrifices. That popular misconception could only be held by people who dare not embark on interdisciplinary journeys.

Thus, by the early 1990s, people like Amory and Hunter Lovins[15] and organizations like the U.S. National Academy of Sciences[16] clearly showed that the USA alone could minimize the greenhouse threat through conservation. In turn, conservation could have saved Americans alone between $56 to 200 billion a year and vastly improved their health and quality of life. For the world as a whole, the saving would have been much higher.

If this sounds counterintuitive, here is just one illustration. Conservation measures, at the very least, could triple gas mileage of the global fleet of cars and meaningfully begin to address the greenhouse threat (as opposed to the bankers’ various scams of making money from climate disruptions by doing … less than nothing). Besides going a long way towards mitigating global warming, such steps could also improve our health and quality of life by cutting pollution, and they could make transportation via cars or buses much cheaper.

So if the technical solution is so simple, why don’t we apply it? Here again is where interdisciplinarity, or holistic knowledge, comes in. The bankers who own the fossil-fuel companies are not content with the trillions they already have. If we increase gas mileage, petrol price would go down to slightly above the cost of production. This would mitigate climate disruptions and save lives and money, but it would slow down the process of money accumulation by bankers and oilmen. Whenever such conflicts arise, the wealthy few almost always win.

Here is a 1996 essay:[17]

For argument’s sake, a conservative and arbitrary estimate is adopted, assuming that the chances of adverse greenhouse consequences within the next century are 10%; of a cataclysm, 1%. Such chances, this review then conclusively shows, should not be taken, because there is no conceivable reason for taking them: the steps that will eliminate the greenhouse threat will also save money and cut pollution, accrue many other beneficial consequences, and only entail negligible negative consequences. Thus, a holistic review leads to the surprising conclusion that humanity is risking its future for less than nothing. Claims that the greenhouse controversy is legitimate, that it involves hard choices, that it is value-laden, or that it cannot be resolved by disinterested analysis, are tragically mistaken.

The “War” on Drugs

Interdisciplinarity again reveals that this subject is far more complex than what we are led to believe.

Here are a few interdisciplinary insights related to this war:

- “The Chinese . . . will never forget their century of humiliation, 1840-1949, when the UK and the US engaged in what is called, ‘the longest running and largest global criminal enterprise in world history’ – enslaving the Chinese people with opium. . . . As a result of bad decisions of China’s rulers and century-long brutal colonial exploitation, by 1949, China was basically a 19th century hellhole, with 100 million opium addicts, people on average died at age 35.”[18]

- Since the USA colonized Afghanistan, that county has become the world’s top exporter of heroin.[19]

- The CIA is known to be involved in importation of drugs into the USA and elsewhere.

- According to a former high-level official in the Nixon Administration, the War on Drugs had two goals:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

- In part owing to the so-called War on Drugs, the USA is the number #1 incarceration nation in the world. It has, in fact, many more prisoners than China, even though China’s population is about four times that of the USA.

- In Mexico, for instance, this war, which had been imposed upon that country by a foreign power, led to the deaths of thousands and is causing the disintegration of its social fabric.

- History shows that the criminal sanction on drugs fails to achieve its alleged goal: Curb consumption of drugs.[20]

· There is also something to be said for the philosophical view that people should be educated about the negative effects of drugs, but that the government has no right to tell anyone which plants they can or cannot grow or use as medications in their own homes. John Stuart Mill: “There is a circle around every individual human being which no government, be it that of one, of a few, or of the many, ought to be permitted to overstep.”

I personally believe that addiction to drugs like heroin is a personal tragedy. But interdisciplinarity suggests that imperial powers have often used drugs to amass fortunes and enhance their power. We should therefore view with some suspicion the motives and sincerity of any government’s war on drugs.

In (U.S.-occupied) Afghan fields, the poppies blow.

Conclusion

Interdisciplinary theory (talking about interdisciplinarity itself) is of limited interest and only deserves a cursory look aimed at understanding its basic principles. It emphatically does not merit a lifelong—nor even a semester-long—study.

By contrast, interdisciplinary practice—the long search for a holistic perspective in classrooms, laboratories, concert halls, art studios, and our very brains—merits our lifelong dedication. If you choose to embark on this holistic road, you’ll gain a far better understanding of our world. You will be able to cross-fertilize your thinking, teaching, and creative undertakings. You will improve your understanding of complex problems. And you will find it easier to think for yourself and to let go of popular illusions.

I invite you to join us.